In the hyper-competitive world of modern entrepreneurship, the mantra has shifted. The era of “growth at any cost” is dead, replaced by a ruthless focus on sustainable profitability. At the heart of this shift lies a single, powerful concept: Unit Economics.

I’m Hammad Hasan. Over the last five years, I have lived in the trenches of startup finance. From building feasibility reports for EV Bots in the USA to crafting financial models for Tadarab in Kuwait and Itsbetter in the UAE, I’ve worked with over 50 global clients to translate their vision into hard numbers. Having sold over 300+ financial models, I can tell you one thing with certainty: an investor doesn’t buy your “big idea”—they buy your unit economics.

If you cannot show that your business makes money on a single-unit basis, scaling it won’t lead to a billion-dollar exit; it will lead to a faster collapse. This article is a deep dive into the mechanics of unit economics and how you can use them to raise funds and scale.

What is Unit Economics? Defining the Building Blocks

At its core, Unit Economics is the direct revenues and costs associated with a single, discrete unit of your business. It is the fundamental building block that tells you whether your business model is inherently “profitable” or “broken.”

The definition of a “unit” varies by industry:

- SaaS (Software as a Service): A single customer or subscriber.

- E-Commerce: A single order or a single item sold.

- Marketplaces (Uber/Airbnb): A single transaction (a ride or a night’s stay).

By stripping away the noise of fixed costs like office rent, legal fees, and administrative salaries, unit economics allows founders to see the Contribution Margin—the profit left over from a sale to cover those fixed expenses.

The Importance of Unit Economics: The Survival Statistics

Why should you care? Because the numbers don’t lie. CB Insights reports that 42% of startups fail due to no market need, 29% run out of cash, and 18% struggle with pricing or cost issues. All three of these primary causes point back to weak unit economics.

- No Market Need: This manifests as a sky-high Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) because people don’t want the product.

- Running Out of Cash: This happens when you scale a business with negative unit margins—the more you sell, the more you lose.

- Pricing/Cost Issues: This is the literal definition of failing at unit economics.

Key Components: The DNA of Unit Economics

Unit economics isn’t a complex mystery; it’s a set of vital signs. When I sit down to build a financial model for a client—whether they are a tech startup in the US or a service provider in the Middle East—these are the specific “organs” of the business we examine to see if the company is healthy or failing.

Here are the key components you must track to ensure your startup is built to last.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

The Definition: CAC is the “price tag” for a new customer. It tells you exactly how much you are spending in marketing and sales to get one person to sign up or buy.

Formula:

CAC = Total Marketing Expenses / Number of New Customers Acquired

- If CAC is High: This is a warning sign. It means your growth is expensive. If you spend $500 to get a customer who only spends $100, you are in trouble.

- If CAC is Low: This is the dream. It shows your marketing is efficient and your brand might be growing through word-of-mouth.

Customer Lifetime Value (LTV)

The Definition: LTV is the total profit a customer brings to your door before they stop using your service. It’s the “big picture” value of a single relationship.

Formula:

LTV = Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) x Gross Margin % x Customer Lifespan

Investors love a high LTV because it proves your product is “sticky”—meaning people don’t just buy once; they keep coming back for years.

Churn Rate

The Definition: Churn is the “leaky bucket” metric. It measures the percentage of customers who leave your service during a specific timeframe.

Formula:

Churn Rate = Customers Lost During Period / Total Customers at Start of Period

If your churn is high (anything over 5% monthly for a SaaS company is usually a red flag), it doesn’t matter how many new customers you get; you are losing them just as fast. Sustainability is built on retention, not just acquisition.

Average Revenue Per User (ARPU)

The Definition: This tracks the average “check size” per customer.

The Math:

ARPU = Total Revenue / Total Number of Customer

In my experience working with companies like Tadarab, we look for ways to increase ARPU through upselling or tiered pricing. If you can make more money from the same customer base, your profitability skyrockets without you having to spend a dime more on marketing.

Recurring Revenue (MRR & ARR)

The Definition: This is the predictable income you can count on every month (MRR) or every year (ARR).

Formula:

ARR/ MRR =Total Active Customers × Average Revenue Per User (ARPU)

For investors, predictable revenue is worth much more than “one-off” sales. It allows for better budgeting and gives a clear view of the future cash flow. This is why subscription models are currently the gold standard for high valuations.

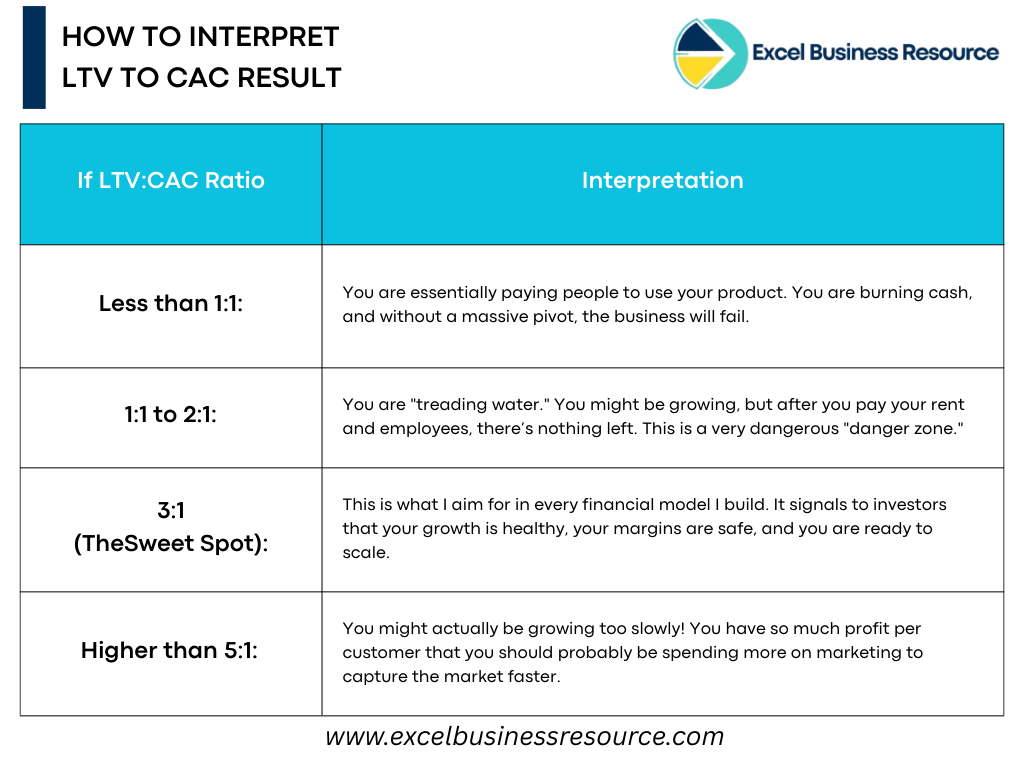

The LTV-to-CAC Ratio: The Ultimate Litmus Test

If you only track one number, make it this one. The LTV-to-CAC Ratio is the final word on whether your business can scale. It asks: “For every dollar I spend to get a customer, how many dollars do I get back in return?”

How to Grade Your Ratio:

🚀 Download Free: CLTV to CAC Analysis Excel Template — Kickstart Your Unit Economics Analysis

Why CLTV To CAC Ratio Matters For Your Valuation

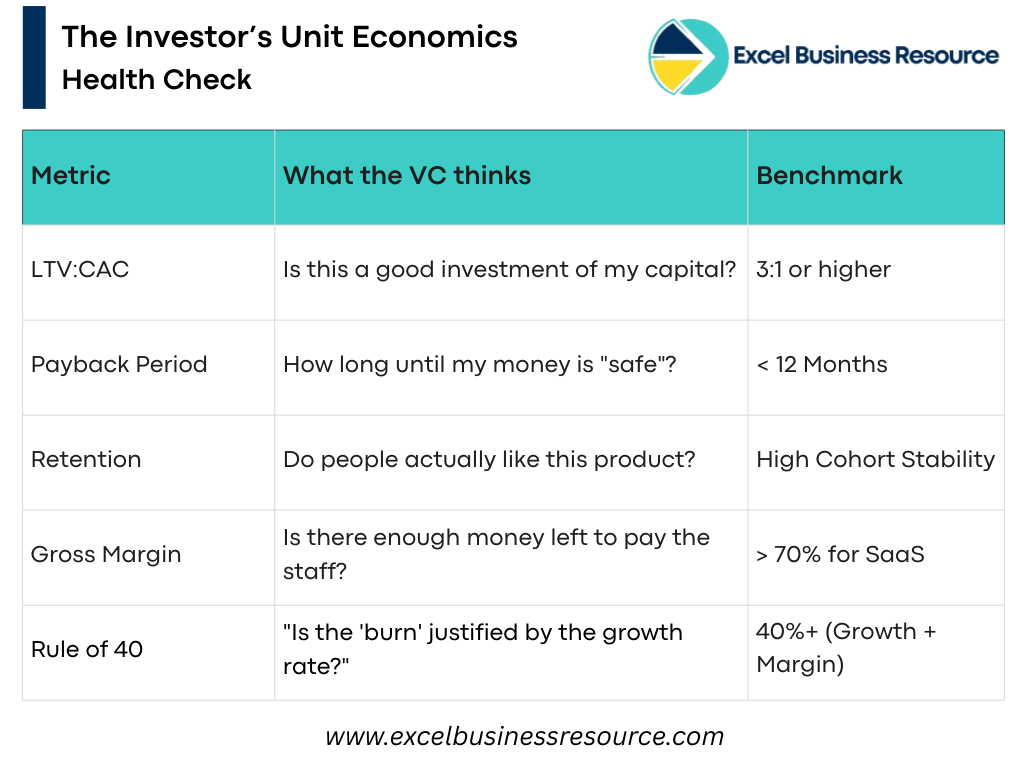

Investors aren’t just looking at your bank account; they are looking at your Efficiency. A strong LTV-to-CAC ratio proves:

- You have found Product-Market Fit.

- Your marketing channels are working.

- You have “room to breathe”—meaning even if costs go up, your business won’t collapse.

When I help founders prepare for funding rounds, we use these metrics to justify a higher valuation. A company with a 4:1 ratio is fundamentally more valuable than a company with a 2:1 ratio, even if they have the same total revenue.

A Practical Example

Imagine you run an app.

- It costs you $20 in Facebook ads to get one subscriber (CAC).

- That subscriber stays for 10 months and pays $10/month at a 60% margin. Their total value to you is $60 (LTV).

- Ratio: $60 / $20 = 3:1.

In this scenario, you can confidently tell an investor: “If you give me $1 million, I can turn it into $3 million in lifetime value.” That is a winning pitch.

How Unit Economics Impact Valuation & Fundraising

When I work on valuation templates for startups, unit economics are the first thing we look at to determine the EBITDA Multiples & Revenue Multiples.

1. The Quality of Revenue

Investors differentiate between “Good Revenue” and “Bad Revenue.” Good revenue comes from units with high gross margins and low churn. If your unit economics are strong, your valuation will be a multiple of your revenue (e.g., 8x or 10x). If they are weak, you might be valued purely on your assets or cash on hand.

2. Efficiency as a Competitive Advantage

In a “down market,” investors look for Capital Efficiency. If you can prove that $1 of investment results in $4 of Lifetime Value, you become an irresistible target for funding. This is exactly how we positioned the financial narrative for my client Itsbetter in the UAE.

3. Scalability vs. Growth

Growth is just a higher number. Scalability is the ability to grow revenue faster than costs. Strong unit economics are the proof of scalability. Without them, “scaling” is just “inflating.”

How Investors Sees Unit of Economics: The VC Perspective

1. The Cohort Analysis: Spotting the “Leaky Bucket”

Investors don’t just look at your total number of users; they look at Cohorts (groups of customers who joined in the same month).

Imagine you acquired 100 customers in January and 100 in June. A VC will ask: “Are the January customers still paying? And are the June customers as high-quality as the January ones?”

- The “Low-Intent” Trap: Often, as a startup grows, its unit of economics actually get worse. Why? Because your first 100 customers were “super-fans” who found you organically. By the time you reach 10,000 customers, you are paying for ads to reach people who might not really need your product.

- What VCs want to see: Stable or improving retention across cohorts. If your newer cohorts are dropping off faster than your old ones, it’s a sign that you are forcing growth on a market that doesn’t want your product.

2. Marginal Contribution: The Law of Diminishing Returns

This is where most “growth-at-all-costs” startups fail. A VC wants to know what happens when you scale the spend.

If it costs you $10 to get one customer today, will it still cost $10 when you are trying to get 1,000 customers a day? Usually, the answer is no. As you exhaust your best marketing channels (like specific Google keywords or niche influencers), your Marginal CAC begins to rise.

- The Test: Can your business remain profitable even if your CAC doubles?

- VC Perspective: They are looking for “operating leverage.” They want to see that as you grow, your fixed costs stay flat while your unit profit stays high enough to absorb the rising cost of marketing.

3. The “Payback Period” vs. “Burn Rate”

Investors use your unit economics to calculate your Runway.

If your CAC Payback Period is 18 months, but you only have 12 months of cash in the bank, you have a massive problem. You will run out of money before your customers have even paid back the cost it took to acquire them.

- My Insight: When I work on financial modeling for UAE or USA-based startups, we obsess over the “Cash Gap.” A VC is much more likely to fund a company with a 6-month payback period because the business generates its own “fuel” for growth much faster.

4. Expansion Revenue: The “Negative Churn” Holy Grail

The best unit of economics don’t just stay stable—they grow. This is called Net Revenue Retention (NRR).

Venture Capitalists get incredibly excited when they see that a customer who paid you $10 last month is paying you $12 this month (due to upsells or seat expansions).

- If your Expansion Revenue is higher than your Churn, you have “Negative Churn.”

- This means your business grows even if you stop spending money on marketing. This is the ultimate signal of a “Category King.”

How to Improve Your Unit of Economics: Three Levers of Profitability

If your current numbers aren’t where they need to be, don’t panic. Unit economics are not static; they are the result of the choices you make every day as a founder. There are three main levers you can pull to transform a struggling startup into a profit machine.

1. Optimize Your Pricing (The LTV Booster)

Many founders are terrified that raising prices will drive customers away. However, price is often the most powerful lever you have.

Think about it this way: If your gross margin is small, a 10% increase in price doesn’t just add 10% to your revenue—it can often have a 100% impact on your bottom line. Why? Because your costs (COGS) stay the same, meaning every extra dollar from a price hike goes directly into your profit. High-value pricing instantly skyrockets your LTV without requiring a single new customer.

2. Double Down on Retention (Killing Churn)

It is a well-known rule in finance that it is 5x cheaper to keep an existing customer than to find a new one.

When I audit a “leaky bucket” business, the first thing we look at is the onboarding process. If you can keep a customer for 24 months instead of 12, you have doubled your LTV without spending a penny more on Facebook or Google ads. Improving your product experience is the most sustainable way to “lower” your effective CAC over time.

3. Build Referral Loops (The Viral Coefficient)

The “Holy Grail” of unit economics is the Referral Loop. If every new customer you acquire brings in one friend for free, your “Blended CAC” is cut in half.

By incentivizing your “happy units” to recruit others, you create a viral coefficient. This allows you to grow exponentially while your marketing budget stays flat. This is how giants like Dropbox and Slack achieved world-class unit economics in their early days.

The Rule of 40: The Investor’s Balancing Act

When I prepare valuation reports for startups that are still technically “at a loss,” we always look at the Rule of 40. This is a quick health check used by VCs to see if a startup’s growth is worth the “burn.”

The Simple Formula:

Growth Rate % + Profit Margin % = 40%

How it works:

- The High-Growth Case: If you are growing at 60% year-over-year but have a -20% profit margin, you are at 40. You are doing great! Investors are happy to fund your losses because your growth is so explosive.

- The Mature Case: If your growth slows down to 10%, you must have a profit margin of at least 30% to stay at 40.

The Rule of 40 tells a founder that it is okay to lose money only if that money is being converted into massive, high-quality growth. If your growth is slow and you are still losing money, your unit economics are broken, and you will fail the Rule of 40 test.

How Founders Can Trace and Optimize Unit Economics

As a financial modeler, I always tell my clients: “You cannot manage what you do not measure.” If you want to reach the level of a Zomato or an Uber, you need a system to track these numbers in real-time. Therefore, I recommend the following tools for analyzing your metrics.

- For SaaS: Tools like ProfitWell or Baremetrics are essential. They plug directly into your payment gateway (Stripe/PayPal) and give you a live dashboard of your Churn, LTV, and MRR.

- For E-commerce: Use Glean or TripleWhale. These tools help you see your “Contribution Margin” after ad spend, shipping, and COGS are subtracted.

- For Early Stage: You can use robust Startup Financial Model Template according to your industry. In the early days, you don’t need fancy software; you need a template that allows you to play with “What If” scenarios. (e.g., “If I reduce my CAC by 10%, how much longer is my runway?”)

- Custom Financial Models: While tools are great, they often lack the nuance of your specific business. A custom-built financial forecasting model

My company excel business resource provides custom financial modeling services. These models allow you to forecast revenue & timeframe for profitability with 100+ critical & variable assumptions i.e. CAC, Price, Market Size, CAPEX, Investment Summary, Startup Valuation, run sensitivity analyses—e.g., “What happens to our valuation if churn increases by 1%?”.

As a financial modeler, I always tell my clients: “You cannot manage what you do not measure.” If you want to reach the level of a Zomato or an Uber, you need a system to track these numbers in real-time. Therefore, I recommend the following tools for analyzing your metrics.

- For SaaS: Tools like ProfitWell or Baremetrics are essential. They plug directly into your payment gateway (Stripe/PayPal) and give you a live dashboard of your Churn, LTV, and MRR.

- For E-commerce: Use Glean or TripleWhale. These tools help you see your “Contribution Margin” after ad spend, shipping, and COGS are subtracted.

- For Early Stage: You can use robust Startup Financial Model Template according to your industry. In the early days, you don’t need fancy software; you need a template that allows you to play with “What If” scenarios. (e.g., “If I reduce my CAC by 10%, how much longer is my runway?”)

- Custom Financial Models: While tools are great, they often lack the nuance of your specific business. A custom-built financial forecasting model

My company excel business resource provides custom financial modeling services. These models allow you to forecast revenue & timeframe for profitability with 100+ critical & variable assumptions i.e. CAC, Price, Market Size, CAPEX, Investment Summary, Startup Valuation, run sensitivity analyses—e.g., “What happens to our valuation if churn increases by 1%?”.

Real-World Case Studies: How Unit Economics Can Make or Break a Startup

Netflix – The Mastery of the “LTV-to-Content” Loop

Netflix is the ultimate example of a company that used high debt to fuel growth because their unit economics were incredibly predictable.

- The Unit: A single monthly subscriber.

- Customer Lifetime Value (LTV): While Netflix spends billions on content (appearing “in the red” on a cash flow basis), but their Churn Rate has historically been among the lowest in the streaming industry (often under 2-3%). Because subscribers stay for years, their LTV is massive compared to their acquisition cost.

- The CAC Factor: Netflix’s CAC is high because they must constantly market new originals content. However, because they own the global rights to their content, the Marginal Cost of serving one additional user is nearly zero.

- Takeaway: Netflix proved that as long as your LTV:CAC ratio stays high and your churn stays low, you can afford to take on billions in debt to buy more market share.

MoviePass – The Fatal “Negative Margin” Trap

MoviePass is a textbook case of what happens when your unit economics are fundamentally broken from day one.

- The Unit: A single monthly subscriber ($9.99/month).

- The Mathematical Flaw: MoviePass paid theaters the full retail price for every movie ticket a subscriber used. If a user in NYC saw just one movie, MoviePass paid ~$15.00 for a ticket they only received $9.99 for.

- The Inverse Scale: In a healthy startup, scaling lowers costs. In MoviePass’s case, scaling increased losses. They had a Negative Contribution Margin. For every new customer they acquired, they lost an average of $5 to $20 per month.

- Takeaway: No amount of “growth” or “data collection” can save a business where the product costs more to deliver than the price it’s sold for. Growth only accelerated their bankruptcy.

Uber – Pivoting from Subsidies to Efficiency

Uber’s early years were defined by buying the market, but they successfully evolved their unit economics to reach profitability.

- The Unit: A single trip or delivery.

- The Efficiency Pivot: Originally, Uber spent heavily on Driver Incentives (essentially a high CAC for the supply side). To fix this, they introduced:

- UberPool: This allowed them to put multiple “revenue units” (riders) into a single “cost unit” (one driver/one car), drastically improving the margin per trip.

- UberEats: By using the same driver network for food, they increased the Utilization Rate. A driver who was idle between passenger trips could now deliver food, spreading the “cost of the driver” across more transactions.

- The Result: By stacking multiple services (rides, freight, food) onto one infrastructure, they lowered their blended CAC and increased the LTV of every person on the platform.

- Takeaway: If your initial unit economics are shaky, you must find ways to increase Asset Utilization or stack revenue streams to make the unit profitable.

Conclusion: Don’t Build on Sand

Unit economics is not just a section in your pitch deck; it is the blueprint of your company’s future. Whether you are building the next big AI bot or a local service platform, the math must work.

If you are a founder looking to raise your next round or simply want to know if your business is truly profitable, don’t guess. Use a structured financial model to validate your assumptions.

I’m Hammad Hasan, and I’ve helped hundreds of founders turn their “units” into millions. Visit excel business resource to download our latest financial modeling templates and start building your startup on a foundation of solid math.